As I grew up in the church, I often felt pressure to sustain a relentless positivity. This is not difficult for me—I constantly reevaluate past experiences to find the positive silver linings. The glass, as it turns out, is always completely full of something! As long as, of course, you acknowledge that air, water, or even dirt count in the equation.

This attitude is rampant in the Christian church. We sing songs of celebration. We tell stories of victory. We remind people that God is the great Healer by shining light on those who have been healed. We focus on the end of the story—GOD WINS!

Why is this Pollyanna attitude so expected in Christian culture? Scripture says so, of course! We have all heard phrases like “rejoice always,” “pray continually” and “give thanks in all circumstances” (1 Thess 5:16-18 NIV). These are beautiful scriptural injunctions and justifiably receive lots of air time in our culture. However, if I properly tend to my own emotional state, I realize that not all circumstances make me (or others in my community) leap for joy. I cannot always genuinely communicate thanks to God for every difficult season. Does that make me less of a Christian? In the interest of obeying these passages “literally,” I would frequently find myself silencing and shoving down sadness, bitterness, or other “negative” emotions.

Is our positivity inaccurate? Absolutely not! God DOES win and we SHOULD celebrate! But it is inaccurate and unhelpful to paint the story of Christianity as only happy. All people sin. Not everyone is healed. Eventually, we all die (even those that Jesus raised back to life, like Lazarus, physically died a second time!). I believe that many people like me could find deeper engagement with the range of their emotional responses to our complicated world by reading and applying the book of Lamentations.

Understanding the context of this book is key. Disaster has befallen the Israelite community: Jerusalem has been destroyed. The face of God feels far away. God’s people are crying out, mourning their deep loss and palpable misery. This instructs modern Christians, firstly, by legitimating the reality of suffering and the depth of grief that it can cause both individually and communally. The modern church is no stranger to suffering; believers around the globe experience grief for many reasons, some being the chaos of natural disasters, the pain of persecution, and confusion in the wake of highly visible moral failure.

The style of mourning presented in this book provides an example to the modern church. In Lamentations 1, the author uses poetry to engage the audience, uniquely conceptualizing Israel’s grief. Specifically, the author symbolizes the exiled Israelite community as a deserted widow, bitterly groaning her fate. This personification invites the community to visualize their pain in an abstract yet understandable manner, giving voice to many of the deep-seated emotions they may not have otherwise acknowledged. By hearing this woman and connecting to her grief, the community is invited to acknowledge their parallel pain and process it more fully. So, the modern church can work to find ways to creatively express grief to invite communities to connect with the pain and suffering in a relatable way.

Lamentations 3 includes a great hymn instructing listeners in the stages of lament. The chapter begins with continued mourning for their fate, pivots to a brief interlude of hope in verses 22-33, and then returns to anguish and another agonizing cry to the Lord. The middle section (verses 22-24) is frequently read and meditated upon in worship services (such as Holy Week). I bet you’ve heard a few of these verses before:

“Because of the Lord’s great love we are not consumed,

for his compassions never fail.

They are new every morning;

great is your faithfulness.

I say to myself, ‘The Lord is my portion;

therefore I will wait for him.'”

Or Lamentations 3:31-33:

“For no one is cast off

by the Lord forever.

Though he brings grief, he will show compassion,

so great is his unfailing love.

For he does not willingly bring affliction

or grief to anyone.”

Yet, just as frequently, we leave out the more “negative” passages like Lamentations 3:7-12 that surround the hopeful passages. You’ve probably never seen this delightful sentiment cross-stitched on a pillow:

“He has walled me in so I cannot escape;

he has weighed me down with chains.

Even when I call out or cry for help,

he shuts out my prayer.

He has barred my way with blocks of stone;

he has made my paths crooked.Like a bear lying in wait,

like a lion in hiding,

he dragged me from the path and mangled me

and left me without help.

He drew his bow

and made me the target for his arrows.”

Yikes. God is shutting out prayers and mangling people? This may be how we feel sometimes, but we surely can’t voice it to a loving God, can we?

After penning these words of utter agony, the author of Lamentations speaks words of hope and trust in the Lord. But stripping the hopeful passage from its tragic context causes the inspirational interlude of Lamentations to lose its significance. How much more compelling are our highest highs when we can compare them with our lowest lows? When we create spaces to recognize the need for lament, we can foster proper engagement with our emotions. By ignoring anger, grief and sadness, we ignore real parts of the human experience. As Pete Scazzero writes:

“When we deny our pain, losses, and feelings year after year, we become less and less human. We transform slowly into empty shells with smiley faces painted on them…But when I began to allow myself to feel a wider range of emotions, including sadness, depression, fear, and anger, a revolution in my spirituality was unleashed. I soon realized that a failure to appreciate the biblical place of feelings within our larger Christian lives has done extensive damage, keeping free people in Christ in slavery.”1

We must, therefore, find ways to thoughtfully tap into the range of our emotions as individuals and as a Christian community.

In a class I took recently, I had the opportunity to practice a couple different methods of applying spiritual disciplines. My favorite practice went by the name of SASHET and required journaling about times in which I felt SASHET: Sad, Angry, Scared, Happy, Excited and Tender. I figured (being a generally joyful person) that finding consistent examples of Angry or Scared would be difficult. And I was shocked to discover that when I tended to my emotions, I found plenty of fodder for all six categories! Though I was surprised that I was not always “happy,” I could more deeply appreciate the times of pure joy because I could accurately understand and express the different facets of my emotional memory. It was not wrong to be sad; sometimes, it was necessary. And though I am genuinely happy 97% of the time, I found greater balance by acknowledging the 3% of times that I am not.

How can you tap into the full range of our emotional space today? Are you able to step outside your current experience, creatively depicting it for greater understanding, as the widow serves the audience of Lamentations? Or, maybe you could help your friends visualize a difficult communal experience through visualization? If you journaled through SASHET, what might you find? How can you honestly express that to God and then articulate the hope you retain in him?

Footnotes:

1 Emotionally Healthy Spirituality, 44.

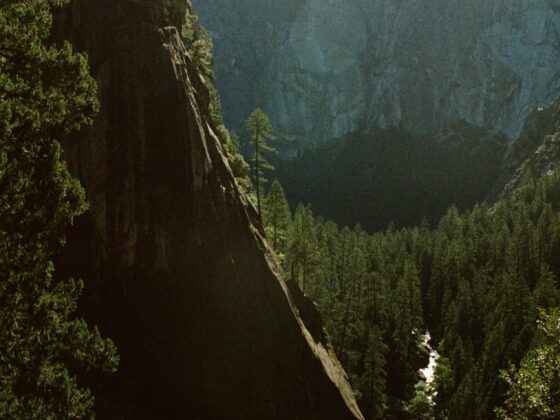

Photo Credit: Emilee Carpenter

Julie isan engaging learner and educator with a love for inspiring groups of all sizes to learn widely and grow deeply. Presenting content that is both fascinating and fun, she enjoys bringing life to a wide range of topics, from FDA regulations, to German beer brewing history, to the beauty of Scripture expounded across eras of the church to the intricacies of sweater knitting. She is currently studying at Denver Seminary for her M. A. in New Testament, though she remains based in her beloved Cincinnati to grow roots with her amazing friends, family and church.