Consider what Jesus means when he says,

“I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.”

John 14:6 NRSV

We will return to this verse at the end of this post.

The Problem

“What is knowledge, really?” “How do we know what we know?” “How can I be sure?” Such questions likely have bothered most of us at some point. These questions are what philosophers call epistemological questions, that is, questions relating to the theory of knowledge. Even though Western philosophy has explored such questions for centuries, modern people seem less confident than ever about their ability to answer them. How come?

James Talbott has argued that much of Western philosophy and the modern world have disastrously accepted what he calls the “proof paradigm.”1 The proof paradigm requires that knowledge be derived from indisputable truths. In short, much of the Western world has demanded that true knowledge is certain. Rene Descartes, Immanuel Kant, and David Hume are three of Western philosophy’s most popular enthusiasts of the proof paradigm. Chasing after certainty, each tried to justify his beliefs by grounding them in undeniable truths. For instance, Hume, during his thought experiments, became so skeptical that he doubted his very beliefs in physical objects, the future, and the rule of “cause and effect.” He abandoned beliefs he could not be certain of, and so, his intense skepticism precluded him from saying anything meaningful about the world.

Hume’s conclusions and those like them are common in our public discourse. Recognizing our inability to achieve certainty, many modern people either adopt relativism (“each person has their own truth”) or skepticism (“who really knows?”). Still, most of us are unwilling to give up our moral values, simple truths we hang our lives on, and, most importantly for many of us, our belief in God.

Our culture’s insistence on the proof paradigm has trained us to believe we can know very little, but our basic instincts tell us otherwise. This situation may leave us feeling stuck, anxious, and unsettled.

Luckily there is a way forward.

The Adjustment

Recently, many intellectuals are moving beyond the proof paradigm. I suggest their theories of knowing can vindicate our most basic human instincts, revitalize the simplicity of knowing, and encourage Christians in their belief in God.

Esther L. Meek, a Christian philosopher, rejects the proof paradigm. Foregoing certainty, Meek defines knowing as “the responsible human struggle to rely on clues to focus on a coherent pattern and submit to its reality.”2 Note the language she uses: “clues,” “focus,” “pattern,” and “reality.” She seems more like a detective than a philosopher. Meek suggests the act of knowing involves mind and body. She offers bike riding as a helpful analogy for understanding how humans come to know anything. One can’t learn to ride a bike by contemplating irrefutable truths or reading a book on bike-riding methods. Instead, each of us must get on the bike, struggle with the pedals, wiggle around the handlebars, scrape a few knees (hopefully just a few!), and, eventually, each of us senses a pattern. One’s pattern may suggest it’s easier to stay upright when pedaling faster. When one feels like they are falling to the left, they turn their handlebars in that same direction to restore balance (counterintuitively, I might add). One even learns how to use the brakes. In a few short weeks, one forgets what life was like before they knew how to ride a bike. Now they glide around the park without much thought. In fact, once one knows how to ride a bike, if they begin thinking too much about what their body is doing as they ride, they may fall.3

Coming to know something is like riding a bike. We gain knowledge as we learn how to operate in the world effectively. As embodied beings in the world we make assessments, select courses of action, and take “personal initiative” to begin forming a coherent pattern of the world.4 Then, having discerned an adequate pattern, we feel a sense of harmony with ourselves and the world; our pattern “opens the world to us.”5 James Talbott argues Sherlock Holmes embodies this knowing process since Holmes’ “reasoning involved sensitivity to clues… and the ability to select the most coherent explanatory narrative,”6 or what we are calling a pattern. For Holmes, knowing is less about acquiring a list of certain facts and more about “making sense of things” as best he can.7 Like Holmes, when our expectations fail, we change them to form a better narrative, a better pattern.

As humans we’re constantly honing our patterns whether we know it or not. For instance, let us imagine we’re carrying a heavy box down a flight of steps, and, reaching our foot out, we suddenly realize we have one more step to go before reaching the ground floor. How do we react? Do we throw the box in the air and say, “see, I can’t know anything!” like our skeptical friends? No. We adjust our footing because we’ve incorporated the new information to form a stronger pattern. Like Meek and her bike riding analogy, Talbott suggests that to know something is not to gather a list of facts but to learn from our mistakes.8 We must accept that “our active, embodied engagement with the world is a skill” that’s improved as one marches through time.9

The Payoff

Meek and Talbott’s model of knowing can work with Christian faith. Again, to know is to detect “a coherent pattern and submit to its reality.”10 But let me be clear; I’m not suggesting we need to adopt an entirely new method of knowing to justify our Christian faith. Rather, I believe Meek and Talbott offer a more accurate model of how knowing truly works, and Christianity makes sense considering this model.

One might respond, if everyone is relying on their pattern, doesn’t this just thrust us back into relativism or skepticism? Yes and no. On the one hand, yes. Like the proof paradigm, Meek and Talbott’s model of knowing does not provide certainty. But remember, no model does. On the other hand, no. This model of knowing does not run the risk of relativism or skepticism because Meek and Talbott are describing the act of knowing as it actually happens, rather than offering some theoretical ideal of knowledge. Moreover, built into this model of knowing is the understanding that each person’s pattern is constantly improving over time. This isn’t succumbing to skepticism or relativism. Rather, each person is doing their best to account for an embodied experience common to most humans.

How does this model of knowing support one’s Christian faith? When we come to realize how knowing actually works, the Christian is greatly advantaged. On Meek and Talbott’s model, the Christian need not feel ignorant or intellectually anxious because they don’t have irrefutable truths supporting their belief in God. Nobody has irrefutable truths to support anything. (Similarly, scientists don’t need to feel existential angst because they cannot ground with certainty the rules of logic, the existence of the past or of other minds, moral values, or the rationality of science itself.) Nobody has the luxury of certainty. Instead, one’s pattern is always under construction as one does their best to create the most coherent picture of reality possible.

Remember, good patterns open the world to us.11 A maximally coherent pattern profoundly opens the world to us by accounting for the bulk of human experience. Most Christians’ patterns have immense overlap. For instance, we believe in the brokenness of mankind and the power of Jesus Christ’s death and resurrection as we await a future restoration of the world. Christians believe this pattern, a basic Christian pattern shaped by the biblical story, can account best for basic human experience. This pattern vindicates one’s recognition of the world’s pervasive sinfulness; makes sense of awe and beauty; justifies one’s belief that their tireless love for their spouse and children is more than a surge of chemicals. This Christian pattern validates the longing one feels for something greater than themselves; explains why one’s mind corresponds to the natural world so well; and explains why Jesus Christ’s selfless sacrifice on the cross speaks to the human soul. Thankfully, Meek and Talbott free us to embrace the coherent pattern of the Christian story. We don’t need to let our uncertainty generate more anxiety. After all, everyone faces uncertainty.

Our model of knowing disarms us from needing to “have all the answers.” Our model enables us to become more empathetic and charitable towards other people and their patterns. We’re free to be curious about others’ patterns. This model helps us interpret people in good faith, since they, like us, are trying to make sense of this world. I submit that if everyone were to embrace this model of knowing, everyone would feel more open to sharing their respective patterns (cf. 1 Pet 3:15) and reflect on their suppositions and beliefs.

I’d like to end with two summative quotes before we return to John 14:6. The first is a well-known one from C.S. Lewis. He states:

“I believe in Christianity as I believe that the sun has risen not only because I see it, but because by it I see everything else.”

C.S. Lewis, They Asked for a Paper: Papers and Addresses (London: Geoffrey Bles, 1962), 165.

Lewis’ understanding of Christ and the Christian story helped him make the most sense of the world around him.

Does Christ and your understanding of Christianity do the same?

The second quote is from theologian Lesslie Newbigin, which reads:

“The confidence proper to a Christian is not the confidence of one who claims possession of demonstrable and indubitable knowledge. It is the confidence of one who has heard and answered the call that comes from the God through whom and for whom all things were made.”

Lesslie Newbigin, Proper Confidence: Faith, Doubt and Certainty in Christian Discipleship (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1995), 105 (emphasis added).

The Christian pattern does not center around undeniable knowledge, but around a person and a story.

Newbigin’s pattern of confidence was in Christ.

Is yours?

Having offered a new understanding of certainty and knowledge, I return now to John 14:6 with perhaps a newfound appreciation for it. Again, it reads:

“I am the way, and the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.”

Interpreting this verse using the language from this post, Jesus claims he’s the ideal pattern, the perfect point around which we make sense of our experience.

Is Christ your ideal pattern? Does he embody the way you should “walk,” the “truth” you should apprehend, and the “life” you should live?

Footnotes

1 William J. Talbott, Learning from Our Mistakes: Epistemology for the Real World (NY: Oxford University Press, 2021), 3–100.

2 Esther L. Meek, Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People (Grand Rapids, MI: Brazos Press, 2003), 13.

3 Meek, Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People, 49–50.

4 Meek, Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People, 58–59.

5 Meek, Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People, 56, 126.

6 Talbott, Learning from Our Mistakes, 125.

7 Meek, Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People, 56.

8 Talbott, Learning from Our Mistakes, 125.

9 Iain McGilchrist, The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World (New Haven, CT: Yale Universit Press, 2019), 223.

10 Meek, Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People, 13.

11 Meek, Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People, 50.

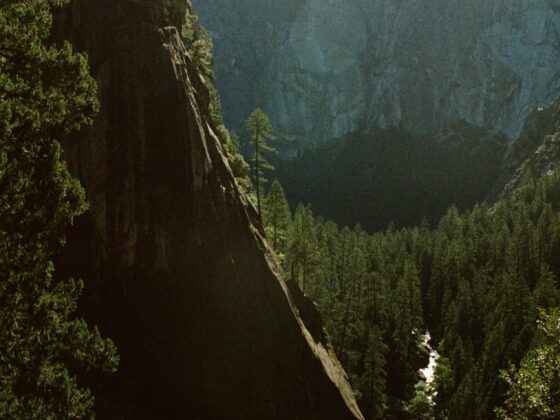

Photo credit: Jenna Martin

CJ Gossage is a Ph.D. student at Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion in Cincinnati, OH. Academically, he is captivated by how the Hebrew Bible generated the many religious expressions of Judaism and Christianity in the Second Temple period and beyond. Practically, CJ enjoys life’s deep, philosophical questions. Theologically, CJ is constantly trying to integrate his academic interests and scattered reading habits with contemporary Christianity.

1 comment

Thanks for writing this! It helps explain the difference between how we think knowledge works and the way it really is obtained.

I find it too easy to react in the “proof paradigm” in general because of how ubiquitously held it is in our day.

Are there any practices you’ve found helpful to integrate this different way of viewing knowledge?

Are there any